Singing Windows: The Beauty of Stained Glass, The Power of Negro Spirituals and The Theology of Resistance

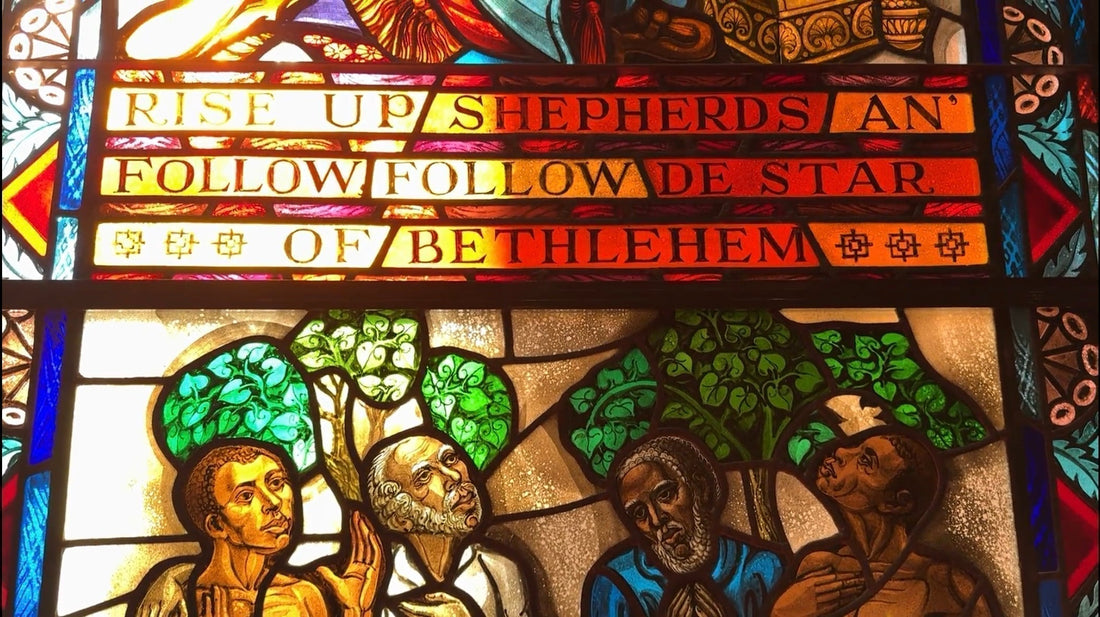

At the heart of this garment lies a story woven from faith, resistance, and the transcendent power of Black musical and visual artistry. Inspired by Tuskegee University Chapel’s “Singing Windows” stained glass installation, this shirt bridges the sacred interplay of the African retentions, spiritual resilience, and the coded language of liberation that defines the Black church.

Photographed by: Alvin Percival, Co-founder

Stained Glass as Storytelling: Illuminating the Ineffable

The stained glass tradition, born in medieval Europe, served as a “Bible for the illiterate,” translating scripture into radiant visuals. At Tuskegee, the “Singing Windows” reimagines this medium to depict the biblical corpus, paying special attention to the Israelite exodus from Egypt, a narrative in which the Black American struggle for freedom so closely identifies. The inclusion of spirituals like “Go Down Moses,” a song steeped in double meanings, transformed biblical allegory into a mirror for the Black lived experience. Miles Mark Fisher, in “Negro Slave Songs in the United States”, emphasizes how spirituals like “Go Down Moses” were “not merely songs of sorrow, but maps to survival,” embedding African cultural retentions within Christian metaphor (Fisher, 1953, p. 25). The Exodus story, depicted in the chapel’s glass, became a shared language: Pharaoh stood for slavers, the Jordan River for the Ohio, and Moses for Harriet Tubman.

This duality of coded resistance beneath sacred metaphor parallels what W.E.B. Du Bois termed the “double consciousness” of African Americans, the “sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity” (Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903). Just as the spirituals’ layered meanings allowed enslaved people to articulate freedom dreams under enslavers’ scrutiny, Black Americans navigated a fractured identity, their survival hinging on the ability to hold both scripture and subversion, revelation and concealment, in a single breath. The Exodus narrative, with its veiled calls for liberation, became a vessel for what Du Bois called “this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge [one’s] double self into a better and truer self”—a spiritual and political act of reclaiming wholeness. As Dena J. Epstein notes in “Slave Music in the United States Before 1860”, spirituals were “a means of secret communication” among the enslaved, encoding “longings for freedom and resistance to oppression” (Epstein, 1963, p. 198). The windows, like the songs, made the invisible visible, offering a theology of hope to a marginalized people.

Photographed by: David Virgil II

Africanizing Christianity: From Drums to Spirituals

The spirituals’ power lies in their synthesis of African musical traditions and Christian theology. R. Nathaniel Dett, composer and scholar, argued in “Listen to the Lambs” (1914) that Black sacred music preserved “the rhythmic complexity and communal call-and-response patterns of West African rituals,” adapting them to Protestant hymnody. This fusion birthed a distinctively Black sonic theology—one that echoed in Tuskegee’s stained glass.

Photographed by: Alvin Percival, Co-founder

William Dawson: Elevating Spirituals to High Art

In the same Tuskegee Chapel where the “Singing Windows” shine, composer William L. Dawson (1899–1990) further crystallized this legacy through his groundbreaking arrangements of Negro spirituals. As director of the Tuskegee Institute Choir from 1931–1955, Dawson transformed oral traditions into orchestrated masterworks, elevating spirituals to the realm of high art while preserving their raw emotional core. His compositions like “Ezekiel Saw the Wheel” and “Soon Ah Will Be Done” married African derived call-and-response patterns with European classical structures, proving Black sacred music could command concert halls with the same authority as Bach or Beethoven. “The spiritual is the finest contribution of the Negro to the musical culture of the world,” Dawson declared, framing these songs not as folk relics but as living art demanding scholarly reverence (Johnson & Johnson, 1942, p. 23). The Tuskegee Choir’s 1932 performance at New York’s Radio City Music Hall, the first Black choir to headline the venue, marked a watershed, asserting spirituals as America’s parallel to European choral traditions.

A Wearable Testament

Our camp collar shirt translates this legacy into wearable art. The viscose fabric’s fluidity mirrors the luminous, shifting colors of stained glass, while the camp collar’s relaxed elegance nods to the dignified resilience of Black worship spaces. The design’s patterns echo the geometric symbolism of the “Singing Windows,” where fractured light becomes a metaphor for collective redemption. Just as the windows illustrated scripture through imagery, the shirt’s aesthetic invites wearers to embody a lineage of resistance. James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson, in “The Books of American Negro Spirituals”, remind us that spirituals were “the articulate message of the slave to the world,” a “sorrowful joy” that transmuted suffering into art (Johnson & Johnson, 1942, p. 21). This shirt carries that message forward, stitching the spiritual’s coded defiance into contemporary fashion.

Photographed by: David Virgil II

To wear this shirt is to drape oneself in a living archive. It is a tactile thread connecting the “Singing Windows’” stained glass—with its Exodus motifs and embedded spirituals—to the Africanized Christianity that sustained a people through bondage and beyond. From Dawson’s choral arrangements to Dett’s symphonic reverence, the spiritual’s evolution into high art mirrors the stained glass’s transformation of folk narratives into sacred iconography. As stained glass once spoke to the illiterate, this shirt speaks to a modern audience, affirming that Black eloquence born of survival remains a beacon of beauty and truth.

Photographed by: David Virgil II

“Weary traveler, Come to the Singing Windows,” the Tuskegee chapel seems to whisper. In this garment, the journey continues.

- David A. Banks, co-founder/designer

Sources Cited:

Dett, R. N. (1914). Listen to the lambs [Musical composition]. G. Schirmer, Inc.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The souls of Black folk. A. C. McClurg & Co.

Epstein, D. J. (1963). Slave music in the United States before 1860: A survey of sources in Notes of the Music Library Association. Howard University Press.

Fisher, M. M. (1953). Negro slave songs in the United States. Cornell University Press.

Johnson, J. W., & Johnson, J. R. (1942). The books of American Negro spirituals. Viking Press.